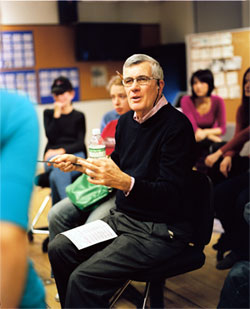

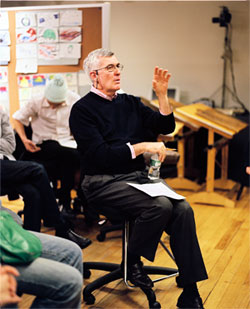

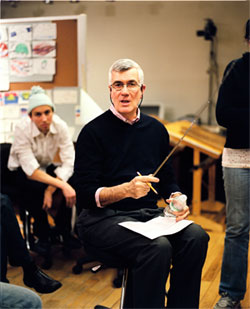

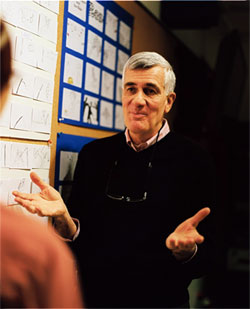

John Canemaker teaching a storyboarding class at NYU Tisch School of the Arts Kanbar Department of Film.

Photos copyright (c) Nick Johnson 917-544-2264

THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION, 4 April 1997. "Designs That Come to Life: 'the Basic Magic of Animation'" by Zoe Ingalls.

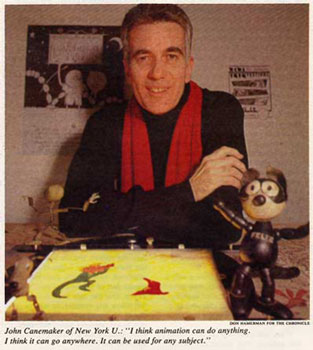

Master manipulator: John Canemaker, head of the animation program at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts, uses his craft to communicate serious matters.Copyright 2000, The Chronicle of Higher Education. Reprinted with permission. This article may not be posted, published, or distributed without permission from The Chronicle.

New York.

John Canemaker relishes the story about a film animator who had a reputation for doing "really zany, crazy, off-the-wall stuff." After getting a call from a producer who wanted him to do a film, the animator said, "Okay, what's it about?" The producer said, "Dyslexia." The animator groaned and said, "Oh, no. You've got to call John Canemaker." Dyslexia, cancer, nuclear war, child abuse - topics that most animators avoid - are topics that Mr. Canemaker embraces.

He is a film animator well known for his intelligent handling of serious subject matter. His animated sequences for the Academy Award-winning YOU DON'T HAVE TO DIE, a documentary about an 8-year-old boy's struggle with cancer, were praised by critics. Mr. Canemaker, a [full] professor and head of the animation program at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts, is also a noted historian of animation. He has published six books on the topic and writes regularly about the field for The New York Times. His most recent book, Before the Animation Begins: The Art and Lives of Disney Inspirational Sketch Artists (Hyperion) appeared in November [1997]. Recently, Animation magazine, a trade publication, listed him as one of the most influential people in animation today, along with the likes of Roy E. Disney, Michael D. Eisner, and Steven Spielberg.

Mr. Canemaker refers to himself as a "traditional" animator - "that means I work with a pencil and paper and a light box" - a distinction made necessary because of recent changes in the medium. Animation used to refer to "any object or drawings that is changed frame by frame," he says. "But now, frames are going away. Videotape has not frames; the computer has no frames. So it's more the thinking about manipulation of the image. We have so many choices now. And animation is everywhere. It's pervasive.

"Animation is in titles. It's in feature-length films, live action as well as animation. Entire films are built around the effects that you see on the screen - TWISTER, for example, or JURASSIC PARK. That's animation. Disney is animation. The Pillsbury Doughboy is animation." The computer is a useful tool - like his pencil, he says - but good animation is not just about drawing or the seamless manipulation of an image. "it's about communicating with an audience," he explains. He tries to teach his students a "vocabulary of motion." For example, "if you turn the character's head this way and leave it for eight frames, it will look like he's thinking."

In a recent animation class, Mr. Canemaker reminds students of the importance of "anticipation" - the small, contrary motion a character makes that anticipates a major movement. If the character is going to stand up, he sinks ever so slightly first. If he's going to jump to the right, he first draws back almost imperceptibly to the left. One student has prepared a short film that shows a man drinking poison. After he drinks, his head shrinks like a deflating balloon. Good, as far as it goes. "Have some anticipation," Mr. Canemaker advises. "Have the head go out, swell, before it shrinks."

Grasping the vocabulary of motion is key, he says. "Drawing is really a secondary ability." He encourages his students to take acting courses, and he brings actors, mimes, and dancers to class so that students can study live movement. "In the '30s at Disney, animators looked at Chaplin films and Keaton films in slow motion. They brought in obese dancers and watched how the flesh moved."

Disney perfected what is called character or personality animation, which lends a character an "intrinsic individuality that is expressed basically by the way it moves rather than just through dialogue," says Mr. Canemaker. The seven Dwarfs are good examples," he says. "Dopey puts on his pajamas differently than Grumpy, and Bashful brushes his teeth differently than Sleepy."

Disney animators have a "live-action approach" to animation, he continues. "They want to convince you of the reality of their world and their characters. They don't want you to think it's a cartoon, so they go to all of these lengths to disguise the cartoony origins of things." His own work "celebrates the cartoon as cartoon," he says. "Animation is not live action, so why disguise that fact?"

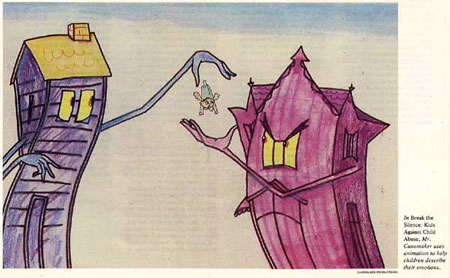

But while celebrating the cartoon, his work is a far cry from what he calls "the cat-chasing-the-mouse type" of animation. "Animation has been ghettoized, for the most part, into a children's category. I really love the challenge of taking serious subject matter and trrying to adapt it to animation. I think animation can do anything. I think it can go anywhere. It can be used for any subject. And it hasn't." In a documentary film, BREAK THE SILENCE: KIDS AGAINST CHILD ABUSE, he used animation to help describe the children's emotions. In one scene, a child tells her mother that her stepfather has sexually abused her. The mother turns into a brick wall, symbolizing her denial.

In YOU DON'T HAVE TO DIE, animation is used to describe what happens during chemotherapy. A green liquid travels down a tube and into the cartoon child's arm. The liquid fills up the child's body as if he were an empty bottle. When it reaches the top of his head, his hair falls out. "He tries as a cartoon to put it back on his head," Mr. Canemaker says. "And then he just looks aghast and runs into the distance. I thought that that was a perfect way to show emotion in animation that live action couldn't do."

As a boy growing up in Elmira, N.Y., he dreamed of working at the Disney studio. (FANTASIA remains his favorite film.) he liked to draw and showed promise as an artist; he made his first animated fiolm -- a history of animation - at age 15. it was largely based on what he had learned from reading books and watching the "Disneyland" television show and Walter Lantz's "Woody Woodpecker Show," both of which were popular in the 1950s.

After graduating from high school in 1961, Mr. Canemaker says, he had no idea what to do. "Nobody in my family ever went to college." He decided to go to New York and become an actor. He got a job as a doorman at Radio City Music Hall and studied acting at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. Soon he began to get work off-Broadway and in television commercials. Tall, thin, and dark, he stunt-doubled for Dick Van Dyke in two movies.

He was drafted into the Army during the Vietnam War, served for two years, then returned to New York and resumed his acting career. From 1967 to 1970, he appeared in 35 commercials - "mostly musical ones, acting, singing, dancing," he says - including ones for Camel cigarettes and Foster Grant sunglasses. He did 15 spots for the American Dairy Association. "I was wholesome," he says. "I was white milk." Wholesomeness paid well. But, one day, a friend said to him, " 'Well, what are you going to do? You've made this money, but you're uneducated. You never went to college.'"

He decided to enroll in Marymount Manhattan College, where, from 1971 to 1974, he worked toward a degree in communications. Between classes, he served as the host of "Patchwork Family," a children's show on a local television station, on which he drew cartoons and sang.

Much later, when some members of his audience attended N.Y.U., they would "do double takes when I walked down the hall. They'd say, 'Isn't that the guy that used to draw?' Then they'd come into the class room humming the theme song." He sings, "Isn't it fun to scribble?" then groans, "Dreadful. Dreadful." "School literally opened the world to me," Mr. Canemaker says. A professor who knew of his early interest in animation offered to give him six credits for independent research at the Disney archive, which has just opened in California. It was a turning point in his life. "There I met all these great animators who I had learned about when i was a kid," he says.

That experience sparked an interest in other pioneers of animation, most of whom were by them quite elderly. Casually at first, then more intently, he began conducting and taping interviews with those animators, in an effort to preserve their history. "I'm their Boswell, in a way, if I may be so bold," he says. "That's pretty cheeky, but in a way I'm a conduit for the information about their lives, and how these films were made, that might have been lost otherwise." The fruits of his research are available to scholars in the John Canemaker Collection in N.Y.U.'s library.

After graduating from Marymount Manhattan, Mr. Canemaker enrolled in the graduate film program at N.Y.U. and continued interviewing pioneers of animation who lied in the area. He did a documentary film on the creator of Felix the Cat, Otto Messmer, who was living in New Jersey. For his master-of-fine-arts thesis, he made a documentary on Winsor McCay, a seminal pre-Disney animator.

"So before I knew it, I started to have this two-track career of historian and animator-film maker," says Mr. Canemaker. He gave up acting altogether. "I was acting through my animation," he says.

When he earned his master's degree from N.Y.U. in 1976, he had a contract for a book, The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy, was working as animation editor for Millimeter magazine, and was busy making short animated films that were shown at festivals.

He began teaching at N.Y.U. in 1980 and eight years later became head of the animation program. His work now is divided between personal films on serious subjects and television commercials for products including Huggies, Diet Pepsi, and Raid.

In Mr. Canemaker's office ay N.Y.U. is a poster featuring two elderly men surrounded by a horde of Disney-cartoon characters, from Bambi to Pinocchio. The men are Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, two of the pioneering animators whose histories Mr. Canemaker has preserved. They signed the poster with "Thanks, John."

Although Disney animators, like Mr. Thomas and Mr. Johnston, helped inspire Mr. Canemaker's earliest work, other influences moved to the forefront as he learned more about animation: John and Faith Hubley, who took on serious subject matter, and George Dunning, director of YELLOW SUBMARINE, who also did a series of short personal films that "played with the medium," as Mr. Canemaker puts it.

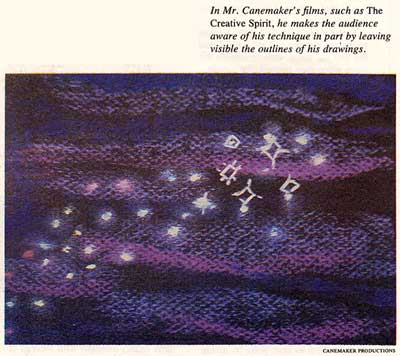

In Mr. Dunning's DAMON THE MOWER, for example, a flip book sits on a table and an unseen hand riffles through a series of drawings. "There was the proof that you could be involved in animation and still be aware of the technique," Mr. Canemaker says.

In his own films, he makes his audience aware of the technique through the hand-crafted quality of his images, which have a painterly, Impressionistic look. It is not unusual for penciled outlines to show through the paint, and some color is thinly enough applied that the paper underneath is visible. "I'm interested in seeing process on the screen," he says. "I'm not afraid to see pencil lines and have it be very scribbly or Impressionistic. I like to see texture from paint.

"Oftentimes, I'll go to a museum and look very closely at the canvases of Matisse or something and see how thin the paint was put on and how much the real canvas shows through. It just fascinates me." Painters refer to this as seeing the "hand" of the artist. Mr. Canemaker likes to see the hand of the animator: "That's what interested me about George Dunning's films, the flip book there in the middle of the table-obviously drawings. And yet the magic was still there, the mystery of inert designs coming to life. "And they're not supposed to. How did it happen? That, I think, is the basic magic of animation - to see something you're not supposed to see. It's not supposed to come to life. It's a drawing. But there it is - boing!"

JohnCanemaker.Com, www.johncanemaker.com © 2000, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007. All Rights Reserved. The website is for education and information use only. All contents may not be reproduced or distributed without the express written consent of John Canemaker. Under no circumstances shall John Canemaker and www.johncanemaker.com, its subsidiaries, or its members be liable for any direct, indirect, punitive, incidental, special, or consequential damages that result from the use of, or inability to use, this site. Website by SJB © 2000, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006,2007. All Rights Reserved.